Last year, I had the privilege of taking part in a tour of the superblocks with architects from Barcelona’s urban planning department. Over three lovely hours, our group—urbanism enthusiasts, cyclists, and professional pedestrians—explored the Sant Antoni and Consell de Cents superblocks. In this post, I want to distill some of the wealth of information shared that day.

What is a superblock anyway?

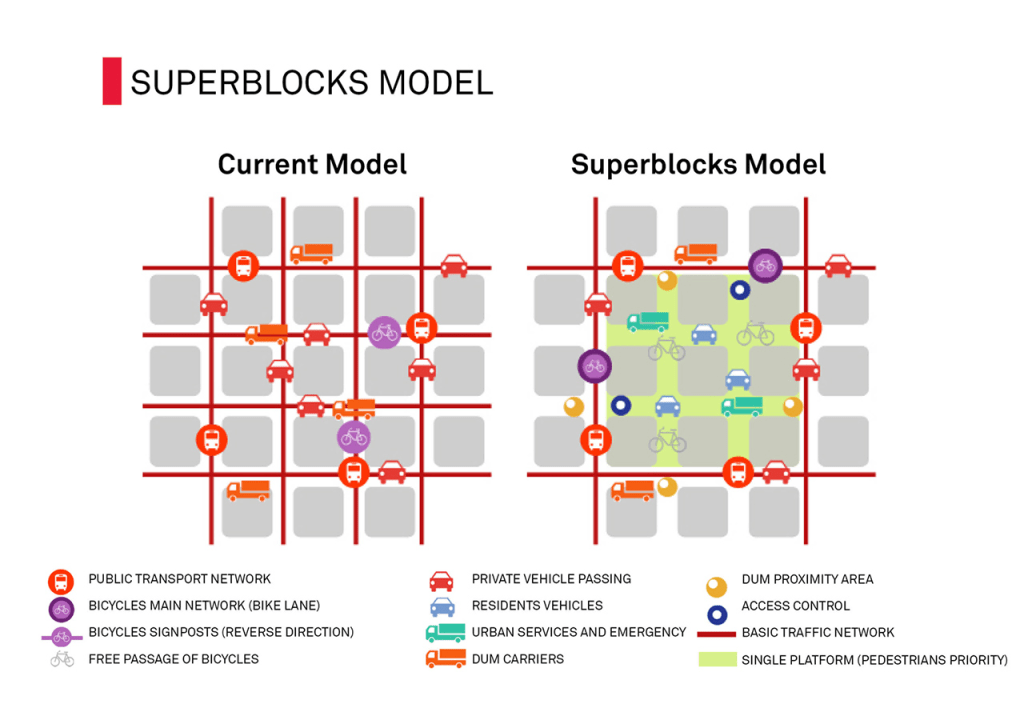

In simple terms, Barcelona’s superblocks (‘superilles’ in Catalan), consist of up to 3×3 ‘blocks’ of housing. Within those blocks, there is no motorised through traffic. Emergency, maintenance and resident vehicles are allowed to access the superblock streets, but at a maximum speed of 10 km/h. The inner streets can then be designed for the needs of pedestrians, cyclists, and people wanting to enjoy the city.

The core aims of the block are to improve the liveability of cities, and to reduce the negative effects of pollution and greenhouse gases within urban environments. Before we look at the superblocks in detail, I’ll take a look back into the history of Barcelona’s famous grid-like design that facilitated the superblocks in the first place.

Barcelona’s grid: utopia gone wrong

Barcelona seen from above is a daunting sight. The rows and rows of uniform apartment blocks look very dystopian, and there’s barely patch of green to be found. This part of Barcelona is actually relatively new. In the 19th Century, Barcelona’s old-town was struggling to cope with the density of people. Disease was rife and life expectancy extremely low, so the city decided to expand out of the old city walls, and connect the old town with the small villages surrounding it. Civil engineer and urban planner Ildefons Cerdà was hired to develop his radical new plan for the city; the creation of a enormous new neighbourhood in a signature grid-like structure with arterial roads across the whole city. The Eixample neighbourhood – which literally means ‘expansion’ in Catalan – transformed Barcelona completely, marking its development into a modern European city.

Cerdà’s original idea was for each block of housing to have two sides and a green space in the middle to provide light, green space and quiet for all. Surprise surprise, a lack of government controls and the desire for profitability meant that each block was soon built up on every side, leaving a small space in the middle.

These days, even the central courtyards have been built up. They’re commonly used as car parks or other businesses, leaving some flats with extremely little or no light. I’ve spent time in flats in Barcelona where there is no natural light at all. In one flat in Eixample I stayed in, an enormous window in a bedroom opened directly onto a lift shaft. Somehow, this isn’t illegal. So while Eixample neighbourhood is still a desirable and middle class area, I find it to be dark and very congested.

Enter the superblock

The superblocks are a practical remedy to Eixample’s woes, and a nod to Cerdà’s original vision for a greener, more liveable city. Salvador Rueda, Barcelona architect, first designed the superblock in the 90s, as part of his design principles for a “city as a system of proportions”, emphasising balance as key for liveable cities. This principle is best explained in Rueda’s own words: “the city can be compared to a paella: the dish may contain the best ingredients, but without salt, it will be bland. And if we add too much salt, it will become inedible. Likewise, if we give most of the streets over to motorised transport, people will get sick and die”.

The first superblock was actually implemented in Barcelona in 1993, but the implementation of the Poblenou and Sant Antoni superblocks in 2018 reached international audiences due in part to political will by Mayor Ada Colau and a savvy marketing campaign.

In the picture above, my tour group are taking a break from cycling along to admire the Sant Antoni block. Our tour guide was quick to point out that pedestrians have priority in the superblock, and that bicycles must adapt their speed accordingly. The superblocks were planned so that adjacent streets have cycling infrastructure, reducing the needs for cyclists or electric scooter riders to zoom through the superblock streets.

Core features of Barcelona’s superblocks include calmed traffic streets, playgrounds for children, benches, and green space. The intersections at each road, which on non superblock streets are reserved entirely for parking, take up 2000 square metres, space which can be used to create plazas in the superblock streets. The square pictured above was being widely used when we took the tour: a group of boys were playing football, elderly people were chatting, and others were simply sitting quietly on their phones.

Data shows that traffic in the superblocks has been reduced by approximately 25%. Of course, the worry is that this traffic will simply be redirected to other streets. To reduce this risk, Barcelona’s transport system was changed from a radial network to an orthogonal network for maximum efficiency, with a public transport stop available every 350-400m. The new network has led to higher bus usage and reduced journey times significantly by increasing speed by an average of 1.3km/h.

The superblocks offer green spaces, but the urban planners had to be very selective about the location of the greenery. In the Barcelona superblocks, only 12% of the streets was usable for urban greening due to underground infrastructure (pipes, cables etc). The task for the planners was to make the superblocks look welcoming, abundant and full of life whilst keeping to strict limits.

Arguably the most difficult part about the superblocks, was being allowed to construct them in the first place. Business owners were worried that their custom would fall significantly if cars weren’t allowed to pass through. The City Council argued that only 5% of customers reached shops by car. In the end, the Council’s perseverance in the face of criticism was instrumental in the creation of the superblocks themselves. Whilst a risky strategy, pushing through despite backlash was perhaps the only way to achieve the desired superblock outcome, and reap the benefits.

As a side note, I really liked this tiny book ‘shop’ I saw on the tour. An unattended bench, a selection of books for a euro each, and the command to ‘Read!’ written on a bit of cardboard.

Trouble in Paradise

This isn’t to say that superblocks are a panacea. One of the most obvious risks is gentrification. As the superblock streets make up a tiny proportion of Barcelona’s streets they risk becoming exclusive enclaves. On the tour this was confirmed to me: trendy wine bars and fancy coffee shops selling expensive matcha lattes were beginning to dominate the area.

The City Council has two practical remedies for this. The first is to build superblocks in different areas in the city – including areas of predominantly social housing – to ensure superblocks can be enjoyed by all and to limit rent rises. Secondly, they impose strict limits on the density of different types of commercial activity, so that streets aren’t overrun by restaurants and bars.

The gentrification problem strongly favours developing an extensive network of superblocks across the whole city, to distribute its benefits evenly rather than keeping it to a couple of highly coveted streets.

The original plan in Barcelona was to do just that: implement superblocks across the whole city and transform it completely. Unfortunately, superblock development has been paused after the new Barcelona Mayor won on a pro-car platform. It’s a difficult time for the City Council’s architects who worked on the superblocks. They told us they are focussing on evaluating the impact of the current blocks fully, to assess how they could be improved for the future.

Having said that, work towards making Barcelona a more liveable city is continuing. Although it might not be so widely publicised, some streets in my neighbourhood are being transformed into green hubs. Cycling infrastructure is also consistently being approved across the city. Slowly but surely, progress is being made.

Contagion

Superblocks are undoubtedly a huge inspiration for urbanists across the world. The architects from the City Council told us (with a slightly weary sigh) that they do a lot of tours for students, city officials and urban planners. I’ve heard and read of cities including New York, LA, Glasgow, Berlin, Paris, and my hometown of Glasgow implementing their own version of the superblock. They may look different to Barcelona’s, but the principles and values of the superblock are spreading like wildfire across the world. Even if progress on the superblocks in Barcelona has stopped for now, their continued impact on urbanism and cities around the world is immense. I truly believe that work on the superblocks will continue in Barcelona one day, and that will make it a better city for all of us.

Leave a reply to hcc2023jm Cancel reply